Sweet Home Chicago ? Evictions

Sweet Home Chicago?

Lincoln Park is a wealthy neighborhood in Chicago. It borders Lake Michigan and has become an extension of the Gold Coast. Looking around at the graystone mansions and tree-lined streets, it’s hard to believe that this was once one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city, a refuge for Puerto Rican immigrants. Signs of the bloody fight that went down from the 1960s to the 1980s as residents fought to hold unto their roots is now only a memory to those who were forced to scatter into other poor neighborhoods like Humboldt Park. Today, more than 50 years later, the largely Puerto Rican neighborhood of Humboldt Park once again faces the same forces that expelled them from Lincoln Park.

This practice of building more affluent neighborhoods on the ashes of poor working-class communities continues across the country today, even during a pandemic. Besides tearing apart communities, another result of this process is ever raising rents. RentCafé, the online rental listing service, estimates the average monthly rent in Chicago at about $2,000. Given the rise of “official” unemployment in Chicago to over 10.6 percent in September and the permanent loss of thousands of jobs, Chicagoans will soon face evictions in record numbers.

U.S. Eviction Crisis

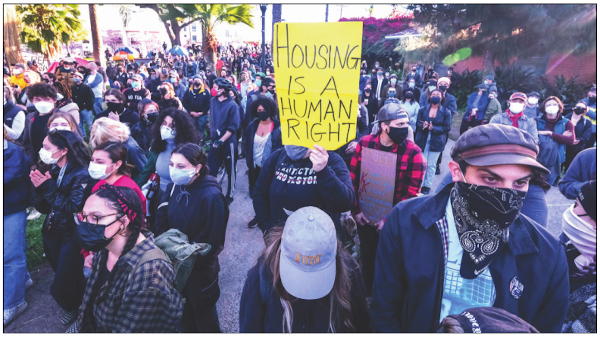

The Aspen Institute estimates that 30-40 million people are at risk of being evicted when the COVID-19 eviction moratorium is lifted, allowing landlords, courts, and law enforcement to rev up the eviction machine once more. Before the pandemic, this eviction machine uprooted families from their homes at an incredible rate. In 2019, more than 23,000 evictions were filed in Chicago. Across the U. S., seven evictions were filed every minute, and three households were actually evicted!

Even with the eviction moratorium, renters are still being pushed out with lockouts, notices on doors, and legal manipulations. And those being pushed out have nowhere to turn. “Due to chronic underfunding by the federal government, only one in four eligible renters receive federal financial assistance,” the Aspen Institute reported in August 2020. “With the loss of four million affordable housing units over the last decade, and a shortage of seven million affordable apartments available to the lowest-income renters, many renters entered the pandemic already facing housing instability and vulnerable to eviction.”

Without substantial relief, Americans will become homeless by the millions, and shantytowns will become a permanent feature of our cities and towns. How did we arrive at this juncture?

Housing crisis

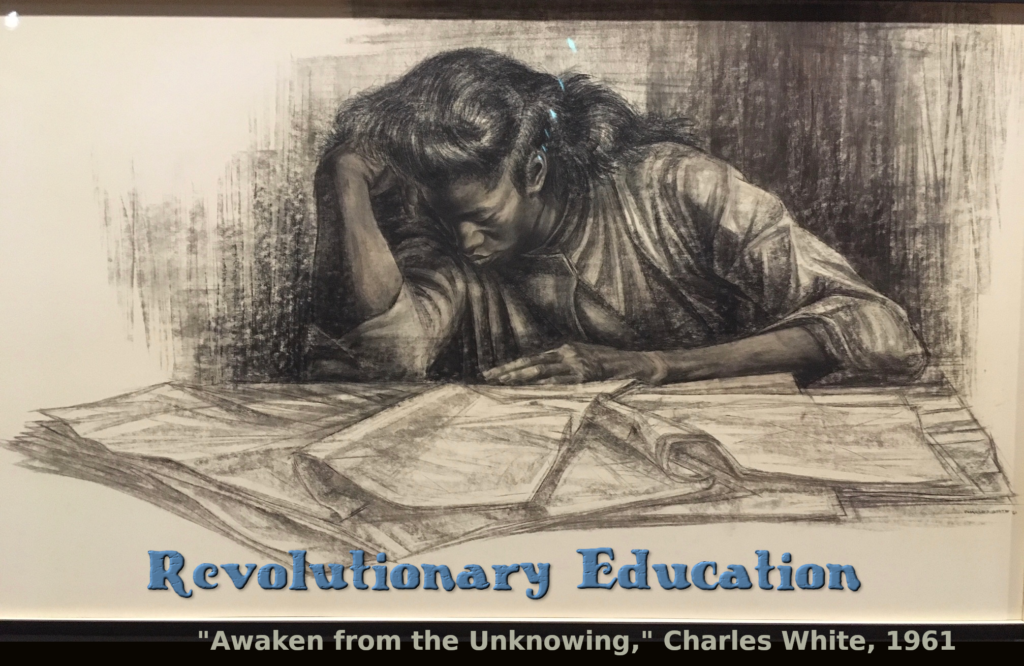

Manipulating property for profit at the expense of communities has a long history. The government works alongside financial institutions and corporate developers, and is responsible for impoverishing communities and all of the resultant social problems. To understand their role, we need a historical perspective.

Going back to 1944, when cotton could be planted, harvested, and baled by machinery, a major population shift took place in the U.S. The new technology combined with Jim Crow laws resulted in a mass migration of African Americans out of the South and into the northern cities, where manufacturing jobs were plentiful. Those making the journey were allowed to settle in immigrant neighborhoods, where a practice of redlining existed.

Redlining meant that people of color were denied access to loans, which stopped them from buying or repairing homes in their neighborhoods. Wikipedia describes it well, “As a result, there was a very low rate at which people…were able to own their homes, opening the door for slum landlords (who could get approved for low interest loans in those communities) to take over and do as they saw fit.”

Redlining helped create segregation of communities by wealth, race, or nationality, inequality of essential services, food deserts, and a political and social isolation that still exists in American cities throughout the nation.

In 1949, the Urban Renewal Act was passed to clear large areas of “slum” housing to make way for modern developments, becoming known as the ‘Negro removal Act.’ “The cleared land was sold to private developers for use in new developments designed to extend the central business district or to attract middle-income residents… the former residents of the area were relocated outside the renewal district,” wrote Mindy Thompson Fullilove, MD in her 2001 book “Root Shock.”

Today we call the process of driving people out of their homes and replacing their neighborhood with more affluent people gentrification. In Chicago, we see this happening in one after another of the inner city neighborhoods. The whole process is planned and orchestrated by government officials, financial agencies, and property developers. Plans to revitalize a neighborhood begin to take shape and be publicly discussed using rhetoric that promises investment in blighted neighborhoods and job creation. One current example taking shape in Chicago is Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s “Invest South/West.” Her campaign promise to bring resources into deprived neighborhoods turns out to be a way to channel city taxes into the working class neighborhoods of Bronzeville and Pilsen to prepare these areas for gentrification. In these examples, “middle class” minorities will often be replacing the poorer people of color who live there now.

Gentrification often takes years, but it relentlessly presses forward. Neighborhoods that have begged and protested for much needed resources suddenly find that schools receive funds, and parks, sidewalks, and streets are beautified. Starbucks coffee shops appear alongside new trendy restaurants and different kinds of shops and services that cater to the new, more affluent residents moving into the pricier refurbished and modernized housing. While this takes place, the old residents struggle to pay higher rents or are forced to move, when landlords evict them so they can rehab their buildings. The little homeowner is alarmed by the rising property taxes and must sell before foreclosure.

The new, more affluent people moving in get the credit for improving the neighborhood, while those fighting to save their homes and their community are accused of standing in the way of progress. The longtime residents are seen as blight and a danger to the new residents. Consequently, the police become more involved with increased surveillance and more arrests. The more interactions people have with police, the more likely people will get hurt.

Yes, this process is a violent one, and very aggressive measures can be used to clear out residents. One example of this was the recent murder of Breonna Taylor by the Louisville, Kentucky police. In a July 2020 article from the Louisville Courier-Journal, Taylor’s family lawyers asserted that the no knock-warrant, which resulted in the shooting death of Taylor “was the result of a Louisville police department operation to clear out a block in western Louisville that was part of a major gentrification makeover.”

While the police play their role, so do some non-profit organizations (that are funded by corporate dollars). They take over the leadership of struggles to save existing public or “affordable housing.” The role of these organizations, along with politicians, is to negotiate the terms of surrender to the inevitable gentrification of the neighborhood. They operate as middlemen providing a buffer between angry residents on one side and the property developers, banks, and gentrifiers on the other. Residents are told to look on the bright side of gentrification and channel their efforts into what turns out to be losing battles to hold on to some turf. In Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood, with a large Mexican population, residents are promised that some of their distinctive cultural landmarks will not be destroyed. If you are forced to uproot and move elsewhere, this is a poor consolation prize.

When the developers, the banks, the politicians, the police, and non-profit organizations all gang up on a poor working class community – isn’t this a war? Although we are the majority, we are not organized to successfully defend our communities against such a powerful alliance. A few communities have successfully organized themselves into an independent force refusing to surrender, and in the end, raised such a fuss that their powerful opposition decided it wasn’t worth it to continue to fight. Of course, gentrification didn’t stop, it just moved to another community.

Banks, real estate investors, developers, and politicians cannot make money from our dream of having stability for our families. Their interests lie in destroying communities, building up new ones, and then destroying once again. For the victims of gentrification, the solution lies in coming together around a shared vision of the kind of community we want and need. We, the people, will have to take over the running of the economy if we are to stop our communities from being ruined. To win a better future, we need a clear understanding of what is in our interests, before we can stand up to those who care nothing for our needs. We will need to take control of our communities, rejecting the idea that anyone who has enough money and power can destroy a neighborhood. We need new ideas to prevail, like the needs of the people are sacred and must always come first. RC

January/February 2021. Vol31.Ed1

This article originated in Rally, Comrades!

P.O. Box 477113 Chicago, IL 60647 rally@lrna.org

Free to reproduce unless otherwise marked.

Please include this message with any reproduction.